There’s a lot to like about Bethlehem. You don’t have to tell that to the people who live there. With all variety of “fests,” Christmas vibes right out of a Hallmark movie, a charming Main Street and a giant hulk of a steel mill repurposed into a thriving arts campus at their disposal, they already know their city is kind of a big deal. But now, following a master class in stamina and tenacity from some history-minded folks, and a denouement that played out thousands of miles away, the rest of the world knows it, too.

It was very early in the morning on July 26, 2024, but LoriAnn Wukitsch and Lindsey Jancay were wide awake. Wukitsch, the president and CEO of Historic Bethlehem Museums & Sites, and Jancay, vice president and managing director of the same organization, were monitoring a livestream of a meeting of the World Heritage Committee in New Delhi, India. They were no doubt joined in their vigil by many other colleagues, city leaders and community members anxiously awaiting word on whether this would be the moment Bethlehem’s Moravian Church settlements would be officially inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

They got their answer around 2 a.m. It was a yes. “I think I shouted so loud that my neighbor probably heard me,” says Wukitsch. Jancay adds: “It was such a meaningful moment. I often say, when you work in the museum field, receiving a text or a phone call at two o’clock in the morning is usually not a good thing, but in this case it was an incredibly celebratory moment.”

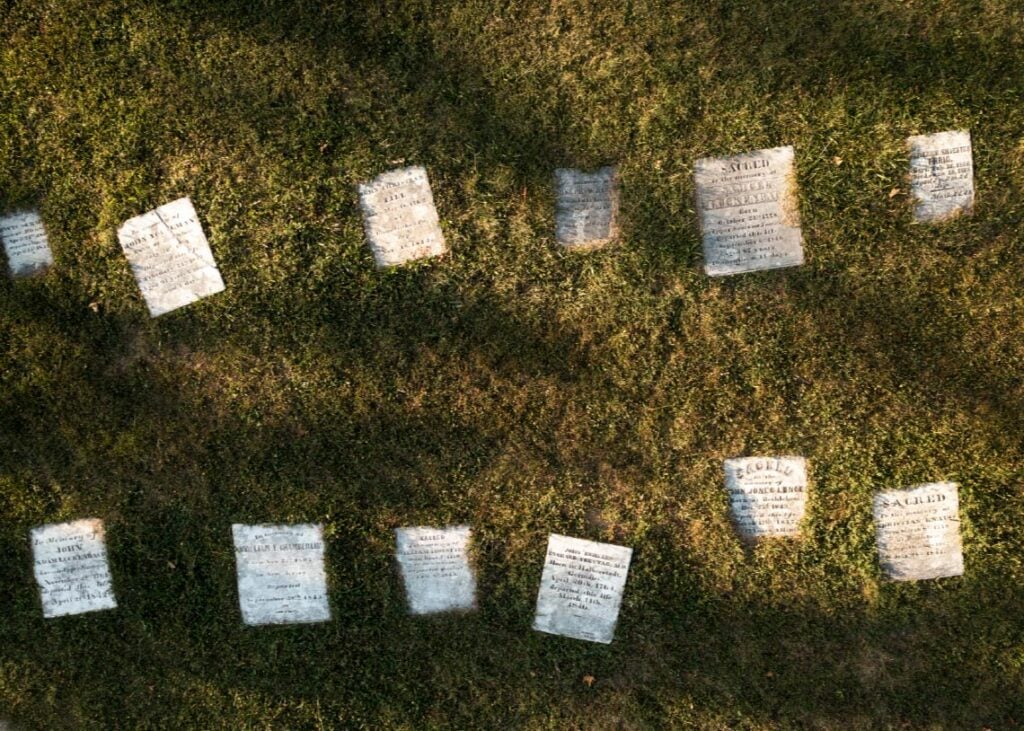

With the go-ahead from the 21-nation body, Bethlehem became the 26th World Heritage Site in the United States, and the third in Pennsylvania. The classification covers a 10-acre site in historic Bethlehem comprising nine structures, four ruins and God’s Acre cemetery. The settlements in the Christmas City join Moravian sites in Gracehill, Northern Ireland; Herrnhut, Germany; and Christiansfeld, Denmark (which was previously inscribed in 2015) as a single World Heritage Site.

The formal inscription ceremony less than three months later brought together guests and dignitaries from around the world for worship, fellowship and tours of the very places now deemed international treasures.

The World Heritage Committee and List, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), were established in 1972 to identify and protect the world’s most significant cultural and natural sites. As of 2024, there were 1,223 sites in 168 countries on the list.

Bethlehem’s inclusion elevated it to an elite status shared by landmarks like the Great Wall of China, the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, and the Eiffel Tower in Paris. “It means that by visiting these spaces, by learning about the people who lived and worked here, we can learn more about ourselves no matter where we come from, and that it can benefit our understanding of the world and how we see it,” Jancay says.

And getting on that list is no easy—or brief—feat. “What I like to say is, it was easier to birth a baby and have the baby graduate from college than it was to get this inscription,” Wukitsch says, laughing.

The campaign to get on the World Heritage List began in earnest in 2002, when Christiansfeld, Denmark, invited Bethlehem to join with representatives from other historic Moravian Church settlements to seek the designation. Both Wukitsch and Jancay name past Historic Bethlehem Museums & Sites President Charlene Donchez Mowers as a significant torchbearer for the project in the years that followed. “It’s really a challenge to keep people’s interest and have them believe that this is going to become a reality,” Wukitsch says. “I credit Charlene for never losing sight of that.”

In 2012, Historic Moravian Bethlehem was designated a National Historic Landmark District. Then, in 2017, the district was added to the U.S. World Heritage “Tentative” List as a potential extension to the 2015 inscription of the Moravian Church Settlement of Christiansfeld. That same year, then Mayor Robert Donchez formed a commission to further the initiative. The application process also required a lengthy dossier, a 300-page tome penned by Donchez Mowers, a World Heritage consultant and two Moravian University faculty members.

Wukitsch, who served as vice president and managing director of Historic Bethlehem Museums & Sites starting in 2010, was named president and CEO in 2022 and helped get the project over the finish line. “I never thought that it was not going to happen, it was just a matter of when,” she says. “And the not knowing when and that long process, that’s what was a little bit unnerving. Twenty-two years in this day and age seems like an eternity when you’re talking to your donors and the community.”

The case could be made for tracing the origins of the mission to achieve World Heritage status all the way back to 1741, when the Moravians first arrived in the place they would christen Bethlehem. The Moravians were known for their excellent craftsmanship and community-building skills. According to Historic Bethlehem, within two years of their arrival, the Moravians built a saw mill, grist mill, soap mill, oil mill, blacksmith shop, tannery and wash houses.

By 1747, they had established 35 crafts, trades and industries, including a butchery, a bakery and a linen bleachery, as well as clockmaking, weaving, carpentry and masonry. Their 1762 waterworks became the first pumped municipal water system in America. The sturdy, stone buildings where they lived, learned and worshipped were built to last. And because of that care and consideration, many did.

Of course, time and the elements will take a toll on even the most expertly crafted structures. Many years after Bethlehem was no longer a Moravian-majority city, and many years before a World Heritage designation was on local historians’ wish lists, early preservationists would need to step in to save some structures from being bulldozed. “A lot of individuals saw the need to carry us through to today,” says Jancay.

Two examples stand out. In 1968, two Bethlehem women, Christine Sims and Frances Martin, saved the 1810 Goundie House on Main Street from demolition by refusing to yield to demolition crews.

Prior to that, Ralph Schwarz, a World War II vet and former Bethlehem Steel employee, led the preservation efforts of the Colonial Industrial Quarter, which had become an automobile salvage yard after the Luckenbach Mill closed in the late 1940s. He’s credited with helping propel Bethlehem toward a designation as Pennsylvania’s first Historic District in 1961.

Historic Bethlehem Museums & Sites will honor his contributions with the Ralph G. Schwarz Center for Colonial Industries inside the Grist Miller’s House, one of the earliest private Moravian family homes in Bethlehem. The building is at the tail end of a lengthy renovation project, with a new capital campaign underway. Previously, it had been propped up by steel beams for two decades. “I think it’s a wonderful tribute to the community after this inscription that we’ll be able to open that up,” says Wukitsch.

According to Jancay, as soon as the World Heritage Site vote became official, they saw an uptick in visitors: “By mid-August we were open seven days a week with offerings. We wanted to make sure we were available to people who were coming to Bethlehem to learn more about the early Moravians.” And those visitors have been coming from farther away, including a couple from Scotland who stopped in Bethlehem before heading to Ohio’s Newark Earthworks, the 25th World Heritage listing in the United States. It’s a trend Wukitsch is confident will continue as they continue to market new experiences, including a one-hour tour that focuses specifically on the Bethlehem sites included in the designation. And the Lehigh Valley’s proximity to New York and Philadelphia can only help. “We’re right in the line of traffic,” she says.

Jancay first discovered Bethlehem's Moravian settlement when she was about eight years old. “I remember seeing these beautiful old stone buildings,” she recalls. “I was already a historically inclined kid, and I was just taken with it. I wanted to get inside, I wanted to learn more about the Moravians.”

Inspiring that same kind of reaction in future visitors is paramount, because, even though the work of achieving World Heritage status is done, the work of preservation has no expiration date. Whether these buildings that were put up with care hundreds of years ago will still be sparking admiration hundreds of years from now is in the hands of the generations to come. “We hope to find the future caretakers of these sites by educating them,” says Wukitsch.

Published as “A World-Class Destination” in the March 2025 edition of Lehigh Valley Style magazine.