Michael Strickland knew that he had found his new home away from home as soon as he set foot in the driveway of the old farmhouse in Bucks County. “I guess I saw the potential,” he recalls. The trick would be getting his then-partner, now-husband, Richard di Fatta, to see that same potential.

Up until that point more than 20 years ago, the two Manhattan dwellers were beginning to wonder if their quest for a weekend retreat would ever come to fruition. They were on the hunt for a rural respite far away from the rush and noise of city life. “Every weekend, we'd do a circle around the city,” says Strickland. Anything within a two-hour perimeter was considered fair game.

Although neither Strickland nor di Fatta is a New York City native (Strickland hails from Florida, and di Fatta was born and raised in Pittsburgh), both had spent enough years there to know it was time for a change. “When you live in the city, you're expected to give your whole life to your job,” di Fatta says. At the time they were wrapped up in especially demanding careers—Strickland worked in marketing and wholesale retail, and di Fatta was in the business of pharmaceutical advertising. Both agreed it was time to pump the brakes and stop to smell the roses (and hydrangeas, azaleas and rhododendrons, as it would turn out).

But they already had perused some 175 properties, to no avail. Then came the fax (yes, fax) from the Multiple Listing Service used by realtors that would change everything. Of course, on paper, the simple farmhouse didn't look like much. “We were looking for Victorian,” says di Fatta. “High ceilings,” adds Strickland. “We thought we knew what we wanted, and it ended up being the opposite of what we bought.”

What they bought in 1996 (after Strickland spent the entire drive back home to Manhattan convincing di Fatta to take the leap) was the quintessential fixer-upper: a 19th-century farmhouse in Upper Black Eddy that was in need of some major TLC. The five-acre property was severely overgrown, and the home itself was cramped and outdated. Still, while they knew that they had their work cut out for them, di Fatta and Strickland were in no hurry to start swinging sledgehammers. “Nothing was done for the first year so we could figure out what we wanted to do,” says Strickland. An architect was hired but then dismissed early in the process so that they could craft the new and improved “gentleman's farm” themselves. They spent their weekends clearing away the dense brush that enveloped the home and property. And while di Fatta pulled weed after weed, he plotted; he mapped out a blueprint of what he would put in their place. “We knew we wanted to do something that was both a summer garden and a winter garden,” he says.

And when it came time to tackle the interior: “We tried to erase the 1970s,” deadpans Strickland. “We took it one room at a time.” He recalls yellow tile and yellow vinyl flooring that got an eviction notice early in the process. Still, the couple was walking a fine line between modernizing the space to fit their style and preserving the integrity of the historic structure, which was built in 1871. “We tried to keep things of the period,” di Fatta says. And, as historic farmhouses aren't generally known for their generous room size and storage space, they had to get creative with what they had. A walk-in closet, a refurbished attic and an enclosed back porch were among the additions that made the cut. Dormers and a front porch and walkway upped the home's aesthetic appeal.

Naturally, ornamental flourishes were needed inside as well. The couple added crown molding throughout the home, as well as decorative trim around windows and doors. Di Fatta handled most of the interior carpentry himself.

“It needed that detail of wood trim to make it shine,” he says.

While they were toiling away on their home and garden, another change was happening: They realized their weekend forays out of the city weren't enough to satiate their growing passion for their bucolic haven off the beaten path. “It just got to the point where we had to make a change,” di Fatta says. “Sundays were a total state of depression. We knew we had the drive back [to New York], the traffic, the tunnels.” So, about four years after first signing their names on the deed, the couple said goodbye to the Big Apple and hello to life as full-time residents of Bucks County. Di Fatta works as a contractor, and Strickland is a realtor. They haven't looked back since. “It's wonderful at this stage, because, for the most part, everything is done,” says Strickland.

The décor of each room reflects their proclivity for the eclectic. The crimson dining room is refined but welcoming, with wall sconces that give the space an inviting glow. The back porch is a homage to the outdoors with fishing paraphernalia and images of bears and moose.

A fireplace in the living room beckons one to sink into the comfy couch in front of it and curl up with a book. The shelves on either side of the fireplace invite exploration; they're crammed with an assortment of collectibles, vessels and figurines that were procured, in many cases, through the couple's travels. “Everything you see in the rooms is something we brought back from somewhere,” says di Fatta. Strickland says family members are also frequent contributors to their collections.

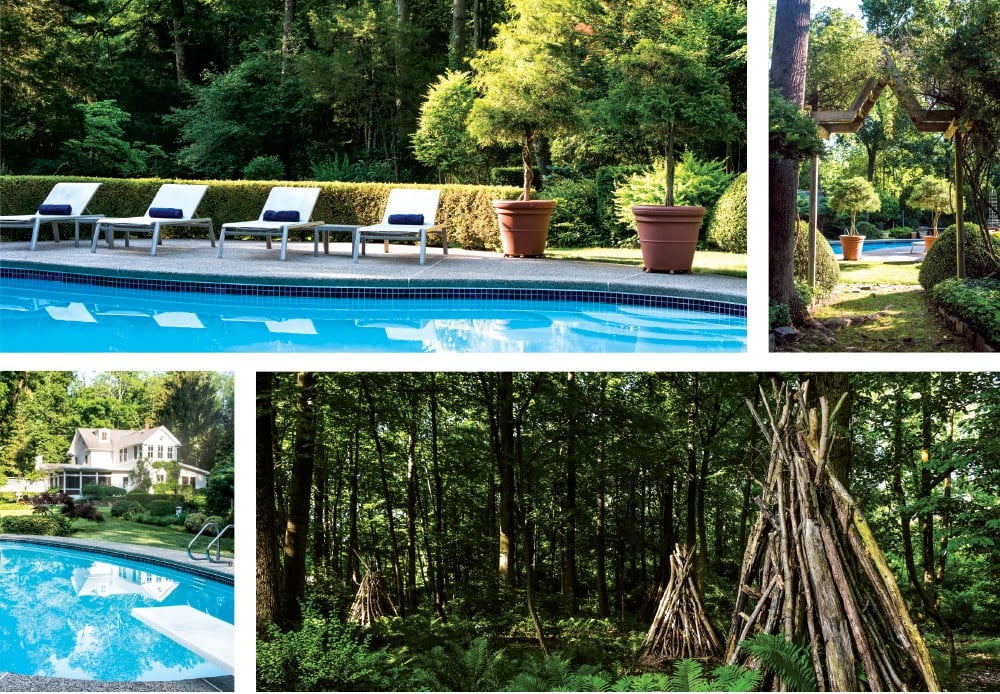

The couple's attention to detail and fondness for variety are also evident in the lush greenery that has thrived all around the home. They estimate they've added thousands of plants to the property over the years, including more than 130 viburnums alone. “We call it the secret garden,” says Strickland. “You walk through a canopy and there's this English-style garden. It's a beautiful garden all year long.” Adds di Fatta, “All the work we've put into it; it gives us back such joy.”

One problem: Deer that frequent the property have found a lot to be happy about, too. Early on, they made a feast of the plethora of hemlocks, junipers, hydrangeas, azaleas and rhododendrons. When traditional deterrents didn't work, di Fatta and Strickland devised their own way to keep the steadfast snackers at bay—they installed green metal fencing akin to chicken wire around the plants deemed especially delicious. While the fencing blends in with its surroundings and serves as a protective shield, it doesn't inhibit the plant from growing through and around it. So now, when hungry critters come foraging for food, the most they can do is munch on whatever has breached the fence's perimeter, and not maul the entire plant. “They don't destroy it; it's more like a natural pruning process,” says Strickland.

The finishing touch for the outdoor oasis is a pristine pool that doesn't feel like an intrusion on the environment around it, thanks to the landscaping detail that helps to blend man-made design with Mother Nature's handiwork. But, like most of the other ventures Strickland and di Fatta tackled on the home front, it was one that required them to virtually start from scratch by overhauling the ‘70s-era design and construction.

Even though most of the major modifications and grunt work are behind them, Strickland and di Fatta know that their ten-year-project turned 21-year-project likely has no real expiration date, because, as most homeowners will attest, once one improvement project is finished, it's not unusual for another to present itself. A new kitchen and remodeled downstairs bathroom are next on the to-do list. But maintaining and enhancing the historic home is a cycle the couple proudly takes in stride, a call of duty they assumed when they first signed their name to the deed all those years ago. “We're basically not owners. We're caretakers,” says di Fatta. “When we leave here, hopefully we pass it on to someone who appreciates the heritage of the house.”