Look over there. Do you see it? Those words in French on the darkened windowpanes? It's not a mirage. We're not in the West Village; the space here is frankly too large for the typical bistro. And we're not in a midtown Manhattan brasserie, either—not enough neon. No, it's Maxim's 22, and it's in Downtown Easton.

This new French bistro/brasserie, which opened in October under the same ownership as Sette Luna (Josh Palmer and parents, Terry and Bud), is situated on the ground floor of the recently renovated Pomeroy's building. Its presence is part of a larger story of a burgeoning restaurant scene in Easton, and the increasingly sophisticated (read: more urban) palate of the Lehigh Valley. It's ironic that we are getting a place like Maxim's now, because French food is fundamental. But it also makes some degree of sense: you can't take yourself seriously as a food community unless you have respectable French fare to go around. For a region that's historically noteworthy for its hot dogs and kiffles, the Lehigh Valley sure has come a long way.

More immediately, however, Maxim's was also born out of a real, pragmatic need. Josh Palmer, 40, whose wife Elizabeth Carlson Palmer serves as chef de cave, or sommelier, says when the two of them began dating, they spent a lot of time in restaurants in Philadelphia and New York City, seeking good trattoria-style meals that neither of them had to prepare. (In the early days of Sette Luna, Palmer was in the kitchen.) “It'd start as a day trip. Then we'd do an overnight. And then it would turn into two and three days, all revolving around food.” Some of those ideas got morphed into Sette Luna. Eventually—shhh! don't tell—they needed a break from pasta and pizza, and returned to New York for bistros. Maxim's, however, is a bistro/brasserie because Palmer found most people he spoke with were unfamiliar with the term brasserie. People think of Paris when they hear bistros, and beer from a brasserie (as the translation suggests), but “I felt best from a branding and marketing standpoint to attach both terms,” he says. Regardless, the usual suspects of French peasant food are on the table, which makes Maxim's a logical complement to what they do well at Sette Luna. “It's nice, but not too nice. It's casual and comfortable,” Palmer says.

“It's nice, but not too nice. It's casual and comfortable.”

There was a big gaping hole in the Valley, just waiting to be filled with French onion soup, escargot, steak frites (served with three aiolis), cassoulet, quiche with a flaky pâte brisée crust, crème brûlée, tarte tatin, and an artisan cheese plate. Let us not forget baguettes; mercifully, the Palmers didn't, either. A bread station full of crusty loaves greets you immediately. The baguette, rosemary sourdough and fruited wheat bread, along with the sandwich breads, are the only items not made in house, but they say it may change in the future—they've provisioned for it.

For now, Executive Chef Bradley Blocker and his team of cooks have plenty to do, with continuous service of lunch and dinner and Sunday brunch. Blocker, 32, grew up in Northampton around good cooks and started puttering in the kitchen in earnest when he was about 10 years old, doing the proverbial tugging at mom's apron strings. “I was a mama's boy so I always was in the kitchen trying to help peel carrots or whatever was needed,” he says. “There was lots of canning, pickling and freezing going on,” he adds. Blocker got his first job at age 13 “totally under the table,” at Downtown Café in Northampton, although the original owners don't run it anymore. “I could walk there from the bus. My mom was a single parent, so I wanted to do something to help lighten the load for her,” he says.

Blocker's name may seem familiar, as it's appeared on menus across the Valley for at least a decade. After graduating from the culinary program at Johnson and Wales in 2002, he worked in the kitchen at the Manor House, but he's also spent time behind the line at River Grille, the Glasbern, Abruzzi on Main, Porters'; he even had a brief stint at Sette Luna a few years ago. When it came time for Palmer to hire his chef de cuisine, he thought of Blocker, who had been operating his own seasonal, well-regarded restaurant, Bradley's on the Lake, for three years up near Lake Wallenpaupack in the Poconos.

It would seem that producing this kind of fare is comfortable for a chef, but it's not necessarily easy. “You definitely have to have experience and knowledge in order to execute it properly,” Blocker says. It's also humbling. “You get this Old World Escoffier feel—you're cooking food that's been cooked for years and years, but putting your own twist on it.” In Blocker's case, he's doing an ale-braised pork shank—a dish that doesn't typically include pork. The primary focus at Maxim's is making the food “phenomenally fresh and well-prepared.” As much as possible comes from a 100-mile radius, whether it's the dry-aged steaks from Indian Ridge Provisions in Telford, the crazy good local-sustainable-organic ice cream from Owowcow in Ottsville, or the succulent duck from Crescent Farms on Long Island. When spring comes, Blocker says they're set to do more farm-to-fork fare from local organic purveyors. And by the time you read this, it's possible the kitchen will have started incorporating more classic preparations such as seared foie gras and sweetbreads.

“The primary focus at Maxim's is making the food ‘phenomenally fresh and well-prepared.'”

Hold on. We have to return to the bread for a minute. If Palmer had opened this restaurant without offering it to diners, holy heck would have broken out. It's well known that Sette Luna does not serve bread as a matter of course unless you order it. In which case, they bring you a basket of hot, olive oil-brushed ciabatta so delicious you forgive them for their indiscretion. It's a choice born out of logistics; Palmer says the oven is just too small to accommodate pizzas and continuous bread baking. The fact that a trio of breads with room temperature soft butter shows up on your table, unbidden by you, the diner, is no trivial comfort. It's an irony that's not lost on Palmer.

“We joke around and say this is the ‘anti-Sette,'—we have bread, and we have music that's not too loud,” he says, citing the two chief complaints people have about Sette Luna. People often complain that Sette is too crammed, and so the tables are bigger and there's more space in between them at Maxim's. The enormous, wrap-around bar is also five times the size of the grotto-like bar at Sette—another marked distinction. You learn a few things after your first foray into restaurant ownership.

When Sette Luna opened in 2006, the Palmers had the good fortune of sliding into a simpatico space formerly occupied by Moscato's—a Tuscan trattoria that closed in 2005 and reopened in 2011 in Palmer Township (and which we profiled in the March 2012 issue). With Maxim's, they had the benefit of a blank slate, and a larger one at that, as that restaurant's capacity is about 150, nearly double the size of Sette Luna.

Palmer, who describes himself as “a frustrated architect,” had a vision for Maxim's, and worked with Maria Diaz-Joves and Ryan Welty of a423 Design in Hellertown, who brought it to life. He describes the process of staying up late one night, looking through a half dozen different blueprints and creating his own hodgepodge with drafting paper and a pencil. Diaz-Joves describes it as a “truly collaborative effort…the idea was to use the beauty of the materials themselves: wood, tile and metal to complement each other and create interesting textures and environments within an open plan, all under an array of warm colors and soft lighting.”

Mission accomplished. Nearly all of the elements of a typical brasserie are present: the marbled countertops, the rooster motif, distressed mirrors, pressed tin, tile floors. From the décor and the menu to the seamless soundtrack of classic jazz and sexy bathrooms (no spoilers!), no detail has been left unconsidered. Maxim's evokes a French-New York iteration of a brasserie, sans the disaffected service that often accompanies such experiences.

Speaking of the design, you may be curious about the 22 wall, a focal point that's hard to miss. Seems that the number 22 has been following around the Palmer family for four generations, starting with Josh's grandfather—it was his football number. And then it was his dad's. Josh was born on February 22; Liz's birthday is also on the 22nd. Their son Maxim was born on 11-11—do the math. When Josh's mom entered a triathlon, she was tagged as 222. And it just gets crazier from there. The address of the building—322—was a happy accident. (They did try to nab a phone number ending in 2222, but the owner wouldn't budge; she'd had the number for decades.)

Numerologists believe 22 is endowed with special attributes—those with a 22 are often called “the master builder.”

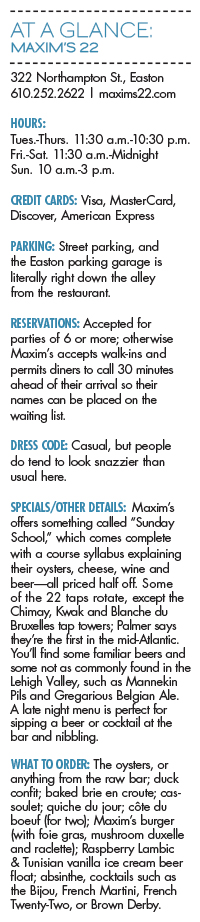

So, of course, there are 22 seats at the bar and 22 taps of Belgian, American and other imported craft beers. Numerologists believe 22 is endowed with special attributes—those with a 22 are often called “the master builder.”

The Palmers have built one good restaurant, and so the success of Maxim's seems all but a foregone conclusion. At the end of the day, a good restaurant should make you forget your troubles, serve you unobtrusively with delicious, soul-satisfying food and transport you to another world. Of course, the extensive beer, cocktail list and 18 wines by the glass (and 130 by the bottle) should assist in the process.

Blocker puts the appeal of his work this way. “It's the freedom of taking these ideas that are in your head and making them happen. It's the kind of art that gets all five senses involved.” Oui, oui, indeed.