Often, Monnahan elevates quality materials above any one particular style, which helps maintain a timeless look. In the kitchen, for example, she used white marble pieces she had saved from the renovation of the master bath to tile the wall beneath the gray-painted cabinets. “I call it my Twombly painting,” she says, because the marble's natural organic designs are reminiscent of the work of artist Cy Twombly. Monnahan is a fan. “I didn't want glass tile because to me, 10 years later, it looks dated. I wanted something classic.” The stone marries beautifully with the granite jet mist countertops. Between the natural materials—including the exposed fieldstone wall and wood ceiling beams—and monochromatic color scheme, the result is cool, minimal, but not so modern as to be jarring. It's what makes a sleek, stainless Viking stove work with a farmhouse-style exposed plate rack.

A long, rectangular island, painted the same shade of gray as the cabinets, runs behind an elongated oval of a table that easily seats six. The weathered wood gives it away as a flea market find, a 19th-century English racing top table. The piece is so big and such a focal point that it might be more accurate to describe the space as a cook-in dining room than an eat-in kitchen, although Monnahan confirms that its function is not formal. “It's all very casual,” she says. “I don't have a sous chef, so I just get up from the table when I have guests and keep the wine and music going.”

“It's not couch potato furniture, but that's what I'd never, ever want,” she says.

The ring of matte black steel garden chairs that surround the table showcase the kind of contrast Monnahan likes so well: wood against metal, round against square, antique next to modern. “I like having sculptural, hard elements mixing with wood and fabrics and leather,” she says.

It's hard to say how much of this arrangement is deliberate and how much is a happy coincidence, given that Monnahan furnished the place with pieces she'd accumulated over a lifetime. “I edited it down to the pieces I truly couldn't part with and kept them in storage,” she says. “I put them all together in my head, but had never seen them all together.” But when she finally arranged everything, she says, “It fit like a puzzle going together: seamlessly.”

Among her prizes are an original Gustav Stickley-designed living room set and library table, all of which she purchased secondhand in the '80s, shortly before the American Craftsman-style pieces became ultra collectible. “I knew I could never afford to purchase them again,” Monnahan says. The library table stands in the entry, while the Stickley settle and matching Morris chair outfit the living room. “It's not couch potato furniture, but that's what I'd never, ever want,” she says.

The Perfect Blank Canvas

Above the massive, if slightly off-kilter, stone fireplace, is one of Monnahan's more recent finds, a set of elk antlers she'd spied at a little antiques shop along the Delaware. Though they were not mounted, and the shop was more than an hour's drive from her home, Monnahan returned three times before finally buying them on impulse one day. “They fit in the back of my Volvo wagon by, I swear, a sixteenth of an inch,” she recalls. Ever detail-oriented, she had Andre Joyau, a furniture-maker friend in Brooklyn mount the antlers on a simple round steel plate rather than the usual wood board. “I loved the organic-ness that it brought into the space,” she says. “Deer go through my property from dusk through dawn.”

The story of the antlers is strikingly similar to how Monnahan acquired the large, round metal sculpture than hangs in the vast empty space above the kitchen, a metal objet d'art that is in every other way the horns' aesthetic opposite: rough, metal, manmade. “I had been looking at that piece in a New York shop for years,” Monnahan says. “Then one day I stopped in the shop and he was moving. Everything was gone except for that one piece. My heart,” she says, “started beating faster.” She came home with the sculpture in tow.

Monnahan has been collecting art for as long as she's been collecting home furnishings (and many of the pieces in her home straddle the line between the two). Much of her collection of black and white photography is displayed on the walls below the balcony that divide the first and second floors; others mingle with prints, framed fabric and more in her spacious bedroom. At some point, she's certain that walls were removed to create the gallery-like space in the old house, leaving her with a bedroom and bath that occupies the entire third floor—the perfect blank canvas.

“I wanted art on my walls, to feel very pampered and luxe,” she says. And truly, there's barely a square foot of unadorned space on one accent wall where the Benjamin (Ben) Moore Ebony Slate paint can peek through. Here Monnahan displays two framed Polly Apfelbaum prints from Bucks County's Durham Press, one called “Rainbow Alley Black” and another, a black and white print called “Little Dogwood 47,” made using cross sections of its namesake tree branch as wood blocks. A photo of Madonna, Martha Graham and Calvin Klein shot by Vanity Fair photographer Jonathan Becker and an anatomical print of the heart round out the display. On an adjacent wall and painted white to heighten the contrast, is a black and white image so simple it's almost abstract, of a horse's torso by photographer Steven Klein.

“I wanted art on my walls, to feel very pampered and luxe,” she says.

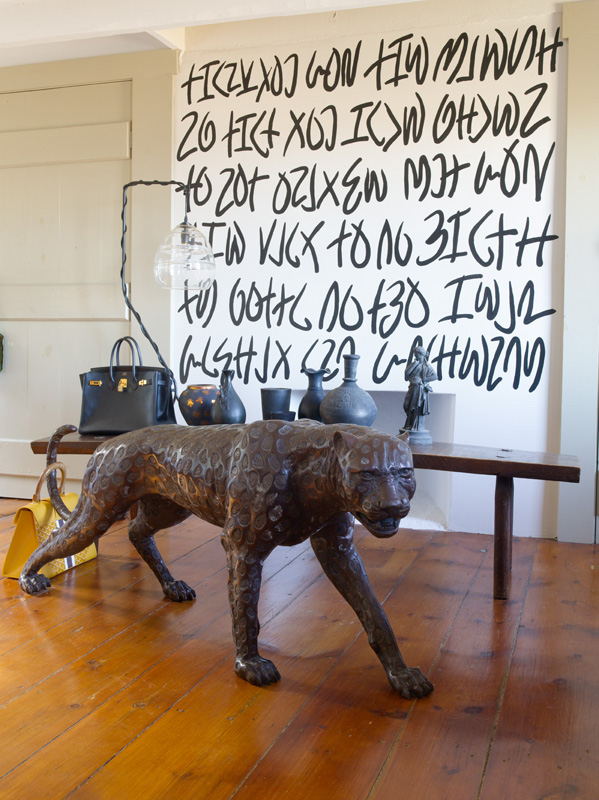

Perhaps the most unique piece was one custom-created for Monnahan by dear friend and artist Virgil Ortiz from Cochiti Pueblo outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico. She had recruited Ortiz to design a fabric collection for Donna Karan, and the two became friends. During a visit with Ortiz and some other friends, she recalls, she brought out a quart of black paint and a brush, and as the group sat there talking, Ortiz painted the piece directly onto the wall over the bedroom fireplace. “He did that in about 30 minutes with no measuring,” Monnahan says. “He calls it a secret language that he and some friends made up when they were younger. It's a prayer. That's why I can't ever move.”

Not that she has any reason to.

In the 10-plus years since purchasing her property, which she now calls Stonehare, Monnahan's interiors proprietorship has become increasingly sought-after, attracting clients like the discriminating director Sydney Pollack and John Demsey, Group President of the Estée Lauder Companies, Inc.

Monnahan says she is excited at the prospect of taking on new projects in the Lehigh Valley (she recently completed the interiors for an upscale retailer called The Denim Project in Easton) and hopes to build her business here while continuing to improve her cherished farmhouse.

And the work is never done—only recently has she gotten around to tackling the seven-acre property, sculpting it with a pickaxe and reciprocating saw, a project that has “given me biceps,” she says—she's more than up to the task. As she says, “I'd like to think I helped feed the soul of this property.”