Like a lot of people, Tug Rice was caught a little off guard by the speed in which the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the U.S. earlier this year. As cases began to pile up in the more densely populated metropolitan areas, the New York City resident packed a bag and made tracks to his parents' home in Bushkill Township. “I think I brought one pair of pants because I thought it would be over quickly,” he says. Several months (and several trips back to his apartment to re-up his wardrobe) later, Rice is still spending the bulk of his time in the Lehigh Valley. Aside from providing him with some peace of mind, his extended stay at his family's home has afforded him a unique opportunity to reconnect with a man who has inspired him both personally and professionally: his grandfather.

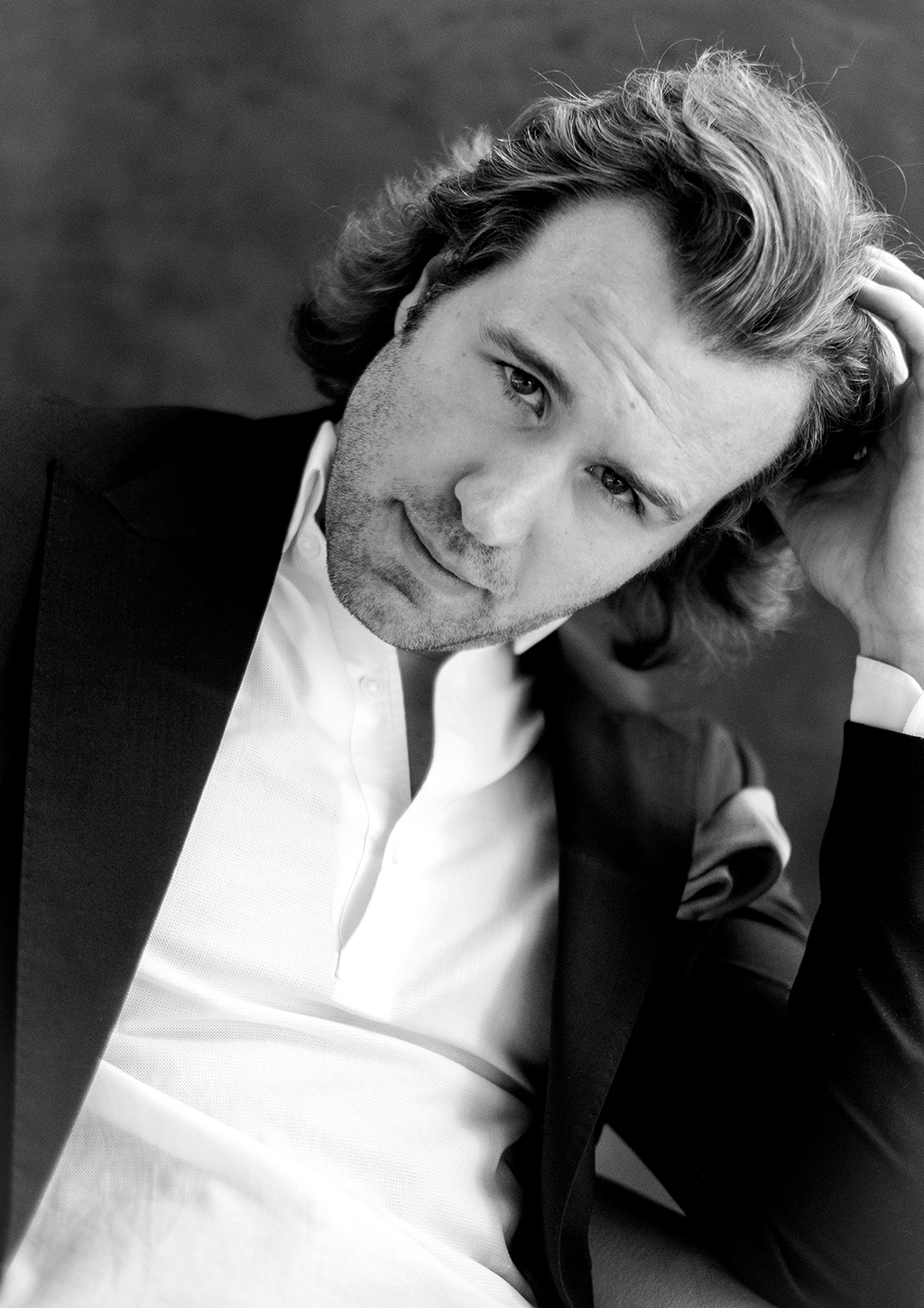

Rice is an illustrator, and a highly sought-after one at that. His work has appeared in publications like Harper's Bazaar, The Wall Street Journal and Travel & Leisure, and his clients include The Carlyle hotel, broadway.com and Harry Winston. His creations conjure up feelings of nostalgia for the glamorous New York of years ago; they're vignettes of life in the city, where even the mundane—taking a bubble bath, lounging in front of the fireplace with a dog at your feet—can seem sophisticated.

They're inspired by the people Rice meets during his (pre-pandemic) everyday life. “You're never at a loss for fascinating characters [in New York City],” he says.

Surprisingly, Rice has never taken a professional art class, although as a kid growing up in the Nazareth area, he frequently had his sketch pad in tow. “I always drew as a kid,” says Rice. “It just never occurred to me that this could be a career.” Instead, he pursued acting and theater, which were the focus of his studies at Lehigh Valley Charter High School for the Arts in Bethlehem and, later, Carnegie Mellon University. But perhaps it's not surprising that Rice returned to the visual arts; after all, it's in his DNA. His grandfather was Donald Johnson, a celebrated painter who won several awards for his work and, among his more prestigious commissions, was selected to paint Gerald Ford's presidential portrait. Johnson's foray into art was a second act for him; he worked at Bethlehem Steel for 20 years before retiring in 1972 as the foreman in the open-hearth division. Rice says his grandfather had long wanted to try to make it as a professional artist, but hesitated to take the plunge. “He had a family and he didn't know if it would be the responsible thing to do,” Rice says.

It would take a vacation to Maine and some very promising words of encouragement to convince Johnson to go all in. Rice says while on the trip his grandfather sought out the home of painter Andrew Wyeth so he could show him some of his work. “[Wyeth] told him to quit his job and become an artist full time. So he did,” says Rice. One of Johnson's murals was painted at the Benedictine Abbey in France. Others were commissioned for St. Luke's Hospital and the Northampton County Courthouse. Sadly, Rice never got the opportunity to get to know the man behind the murals. He was two years old in 1993 when Johnson and his wife, Margaret, were killed in a car accident in East Allen Township. Twenty-seven years later, Rice still laments the loss. “He probably would have taught me how to draw and paint.”

And yet, as he wanders around his parents' home, ticking off each passing day of the pandemic, he's feeling exceptionally close to his grandfather; Johnson's work is featured prominently around the house. “There are always things that I didn't notice before,” he explains. Rice recognizes the divergence in their styles—"Our work is very different. His work was moody. He painted in oils.”—but he also recognizes that his grandfather may have made it possible for him to seek a career as a professional artist. “I never had anyone telling me to be a lawyer or a doctor,” he says. “Not every artist has that support growing up.”

Rice moved to New York City shortly after graduating from Carnegie Mellon in 2012 to pursue acting. But he started to wonder if he was in the wrong line of work after friends took notice of his ink and watercolor prints and paintings and began commissioning him. “It was usually a personal project,” he says. “Where they had their honeymoon, or another place that was special to them.” In seeking out subject matter, Rice also began paying attention to the world around him. “They always say with writing, write what you know. So I thought it's the same with art,” he says. At the time, he was immersed in the theater, so that guided his creative output. One of his pieces, a painting of an audience watching a play, was accepted into a group show in Jersey City. The painting sold, and Rice was offered a solo show in New York City's West Village. After that, he got an agent, beefed up his portfolio and hasn't looked back. “I haven't doubted it at all. I'm almost always working on something for somebody,” says Rice.

This year alone he's had a number of standout projects: he designed coffee cups for specialty coffee purveyor Le Petit Camion in Qatar, and he contributed artwork that was used during Steven Sondheim's 90th birthday celebration tribute concert. The latter, a virtual event featuring performances from a number of A-listers, streamed in April as the pandemic continued its march across the globe. “People were really starved for entertainment, so that was cool to be a part of,” Rice says.

Rice now works exclusively digitally. That comes as a surprise to some who discover his illustrations for the first time, which is probably a sign that he is quite proficient in his craft. “It's challenging to come up with something that feels handmade,” he explains. Rice says it's an issue of practicality: It's easier to interact with clients and make the changes and alterations they need when working with digital files. He wonders what his grandfather would think of the technology that has reshaped the art world since he last held a paintbrush. “I think he would have found it really interesting,” Rice says. “He was always curious about different ways of working and learning new techniques.”

A digital illustrator can also work on-the-go with ease; after all, packing up a laptop is a lot easier than trying to condense a studio stuffed with paints, brushes and canvases into an overnight bag, which certainly came in handy when Rice bid a temporary adieu to New York City earlier this year. But Rice is emphatic that he'd be spending a lot of time in the Lehigh Valley, pandemic or not. Even after moving away, he found himself visiting mom, Patricia, owner of Emily's Ice Cream in Nazareth, and dad, Randy, principal of Allentown Central Catholic High School, often. His sister, Rebecca Orwig, also still lives in the area. “The Lehigh Valley is home,” Rice says.

“It's nice to get out of the city. I love New York. I've always loved New York. But there are times when you have to get out of the noise. Sometimes you have to just breathe.”