In 1997, I met a talented young photographer who was working as an assistant for the legendary Larry Fink. I was curious about her interaction with this intriguing artist, teacher and revolutionary. She regaled me with stories about his acclaimed work as well as amusing anecdotes from traveling and interacting with this affable, electric man. It was only after she introduced us late one summer night that I realized I had seen him all over Easton for many years. He was the man I brushed past numerous times quietly exploring the dusty stacks in a second hand bookstore. He was that guy moving through the shadows of a dimly lit downtown loft party in the small hours of the morning. So he's the guy unassumingly shooting pictures at that amazing jazz concert. That's Larry Fink!

The range and quality of his astonishing work has firmly established his place among the greatest photographers in history. Fink has photographed supermodels, insects, the social elite, rural neighbors, revolutionaries and alien landscapes. He has captured the shape-shifting incarnations of celebrity and anonymity. Politicians at the height of their power and the disenfranchised at the depth of their obscurity, receive equal weight when Fink is behind the lens.

Fink is a child of revolution. His earliest recollection (from 1943) is of being a baby in a bassinet on the floor. There was a blackout in Brooklyn and sirens were howling. His father and mother, far from alarmed, were happily dancing in the darkened room to the lively sounds of Chick Webb.

His parents were colorful characters—idealistic communists with great loves for art and culture. Their home was full of creative artifacts and they enjoyed relationships with many socially conscious painters such as Moses Soyer, Raphael Soyer and Phillip Evergood. These vital artists hung out in their home, enjoying both fellowship and alcohol. The young Fink also had the good fortune of visiting their studios as well as frequenting jazz clubs (where he met Louie Armstrong) and the symphony.

His mother quit the Communist Party (his father was never an actual member) because they were too puritanical. She was in the habit of wearing minks and heading down to Florida to gamble and party. She did not understand why the members criticized her activities. “This is the way everyone should live!” she frankly proclaimed. Parting with the party did not quench her political fervor—far from it. She continued to be an influential leftist organizer until she died at the age of 86.

For nearly 40 years, his sister, lawyer Liz Fink, has indefatigably fought for the underdog. She has been involved in numerous important cases. Towering among them is the Attica Brothers lawsuit. She stayed with this groundbreaking case for 26 years until it resulted in the largest prisoners' settlement in US history.

Teaching was always a part of the revolution, a way of changing the world.

He picked up his father's camera for kicks at the age of 12. He often ran the streets taking pictures with his next-door neighbor, Larry Levine. At this very early stage of development, he won a photography contest sponsored by Kodak.

Fink was an unruly kid. By the age of 16 he started stealing cars. In response to his delinquent behavior, his parents sent him to Stockbridge School. This progressive environment had an international flavor and rigorous educational standards. Without crime on his mind, Fink became a superior student and increasingly obsessed with his art.

He briefly continued his education at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Two months into his studies there, Fink fell to the call of the open road. He eventually landed in Mexico with his beatnik buddies for six hazy months before heading back to New York. While he flatly states that his work from this period was not well organized, the images are sensational. They ooze Boho abandon and disheveled romance. Many of the shots look strangely contemporary. As is the case with much of Fink's work, the formal compositions are flawless.

In the early 60s, he secured his first apartment in New York and hit the streets to snap the locals and find work as a photographer. At this time, the camera was not ubiquitous and did not attract much attention. According to Fink, people had a much more relaxed attitude when you pointed it their way. He explains, “In the 60s, the presence of the camera on the streets of New York City was not a license for exhibitionism or a segue into some instant mini-fame or paranoia—three of the elements that now permeate the arena of being a photographer. The other element of course being commonality, where everybody has a camera and pictures are being spewed all over the face of the earth, and thankfully so. On the other hand, it brings criteria of photography all the way down to the level of common aptitude.”

Fink was soaring above ordinary aptitudes when he volunteered his camera skills at the Lexington School for the Deaf. There he met Father John Hallerhan. He eventually asked Fink to photograph him for the highly regarded Jubilee magazine. Subsequently, Father Hallerhan introduced him to the Three Lions Agency (which was run by three brothers who escaped the Holocaust). They recognized the utility of his burgeoning abilities and opened the door to a new future for Fink. Through this agency he photographed for an array of Catholic and Methodist magazines.

In 1962, he started teaching at HARYOU ACT (part of the Civil rights movement taking place in Harlem). There he instructed budding photographers on how to become effective journalists and documentary revolutionaries. He immediately fell in love with teaching.

“Teaching was always a part of the revolution, a way of changing the world. Teaching was about curiosity about the people I was teaching. I used photography as a tool, but basically its about studying people—which is what is my life has auspiciously been and continues to be about,” Fink says with enthusiasm.

He taught throughout the 60s at the New York Public Theater, The New School and Parson School of Design (Cooper Union).

He married his first wife, painter Joan Snyder, in 1968 and moved into her Chinatown loft. Fink's photographs were featured in The New York Times Magazine and he was working hard to land commercial work in the city. The pursuit was burning him out and his wife suggested he stop and work on some of his own images for a while. First he turned the lens on his family. Next, he developed the desire to document the bourgeoisie. He explains, “I felt at some point they would leave the planet and we would have a new order of the day. I was that kind of crazy leftist. Not unlike Atget, I was going to photograph these venerable trees of the bourgeoisie.”

His teaching gig at Parson brought him into contact with this thin slice of international culture (first generation aristocratic immigrant—with and without money). Fink attended their costume parties and galas. The thick pretense of social status and class attached to these gatherings was palpable. With admirable neutrality Fink refers to these photographs as “the archives of Gaiety.” He spent several years capturing these “charmed” events.

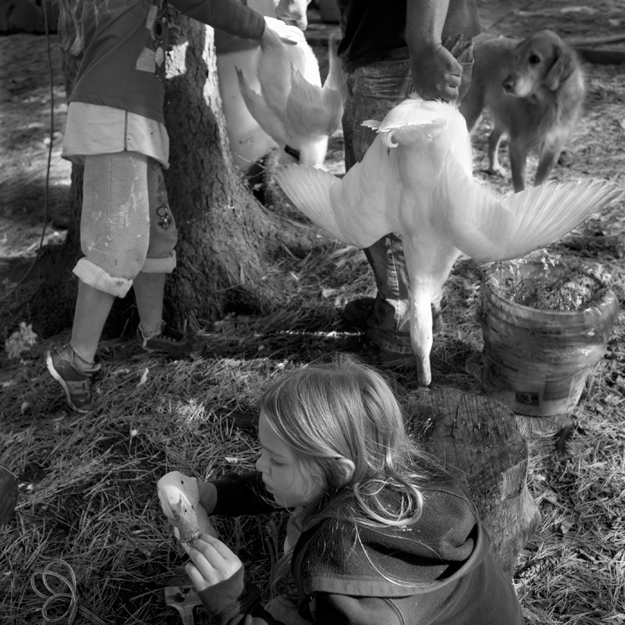

In 1974, he and his wife purchased a farm (where he still resides) in Martins Creek. Initially, Fink did not share Snyder's enthusiasm for moving to the country. If he had to go, however, he wanted to settle someplace extreme. The farm, in terms of solitude and stillness, is worlds away from every external echo of urban life.

It's a sprawling, funky place. These deeply seductive acres are where Fink started to make beautiful pictures of landscapes and creatures. This was also his entry into the world of jacking up barns and cleaning up horse manure. Without much money on hand for help, Fink found himself doing just about everything, including electrical work, carpentry, plumbing and wood cutting. Some days he spent up to 12 hours performing these arduous tasks.

In striking contrast to his fresh rural preoccupations, Fink would steal away to the city for a day or two, to attend balls, dressed in a tux, to continue documenting the bourgeoisie. He says he did not approach this work with a Marxist prerogative. He explains, “I can't photograph, except through my heart. My heart is not compartmentalized or atrophied by ideological beliefs. A heart is in between two sets of eyes, I don't care if it's Republican or fascist eyes—it still has an intermingling, and I work with that.”

When he found himself in need of a cheap lawnmower for the farm he encountered the Sabatine family of Martins Creek. Fink was taken with the clan's charismatic, offbeat, uninhibited style, so he brought his camera along to document his visits. He photographed them for several years, capturing amazing moments at parties, graduations and dinners. These images are replete with messy, joyous life and complex emotional content. The photographs eventually found a home in his seminal book Social Graces.

My heart is not compartmentalized or atrophied by ideological beliefs.

The upper crust of New York society at play comprises the other half of the book. Pristine emptiness and effete fatigue pervades these pages, documenting their gatherings in Washington, New York and East Hampton. While these are brilliant photographs, I find them incredibly depressing. Fink's eye favors neither social pole, but unflinchingly exposes bourgeois decadence in all its bejeweled vacancy.

Around this time, Fink was honored with two John Simon Guggenheim Fellowships in 1976 and then again in 1979. (He is also the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts Individual Photography Fellowships in 1978 and 1986.) Additionally, in 1979, he shared these captivating images in a one-man show at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

At this juncture he also started the photography program at Lehigh University. He went on to teach at Yale and began to shoot his provocative, awe-inspiring pictures of praying mantises (compiled in his mysterious book Primal Elegance).

In the 90s, Vanity Fair magazine made Fink a part of their stable of photographers. He was often sent to solve problems other artists could or would not fix. He says that although many of the stories he covered were odd or pedestrian—without luster—they were still important and he enjoyed them immensely.

The magazine was wise enough to send Fink to cover Oscar parties. These moments are deftly gathered in the award-winning book The Vanities: Hollywood Parties 2000-2009. This unusual, revealing collection transports the viewer far from the shiny surfaces of placid and agitated celebrity that clutter the checkouts at the supermarket. Without a trace of cruelty or irony, Fink brings us into this anfractuous world where the shadowy realms reveal as much as those illuminated by the flash of the camera. He masterfully hunts among the aleatory moments for magic.

“People are more and more toward non-chance. Everybody is setting up their picture in one fashion or another. I more and more passionately, at each juncture of my aging, go toward working with chance—the physical impression you get from first immersion into an experience. The chance of simply being alive,” Fink explains.

While the stunning photographs of Natalie Portman with Meryl Streep, Julie Delpy with Ethan Hawke, Chuck Close and Robert Altman have an undeniable visceral appeal; it is the pictures of strained skin against couture, the lovely childlike lost quality of Lindsay Lohan and the

awkward coupling of Bill Maher and CoCo Johnson that keeps me flipping through the pages. The entourages and onlookers populating the perimeters of some photographs also exert a curious tug on the imagination.

Fink's art is ignited by empathy. He says with great clarity, “I have a weird way of transferring my experience into that of another and co-joining it. That's why my photographs in their body content, not the formal factor, seem to be alive; why they seem to be experiential and not just pictures. I am not looking for pictures. I'm looking for contact. I'm looking for flesh. I'm looking for the soul—something that has to do with destiny.”

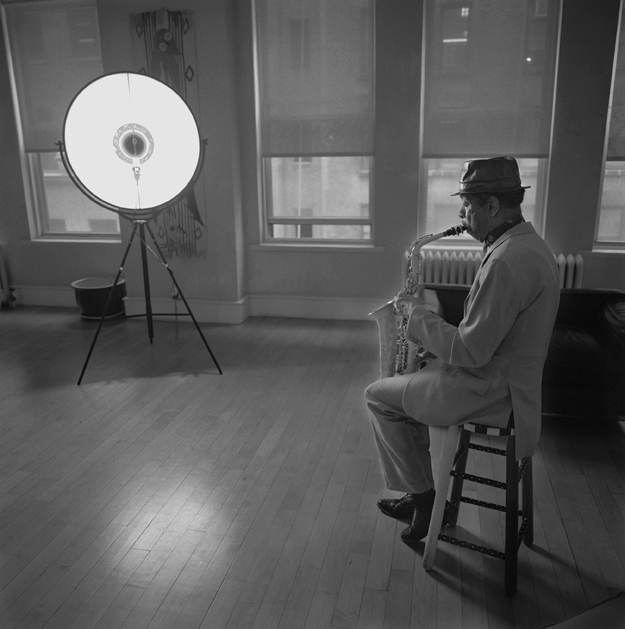

That essential contact between artists is evident in Fink's fantastic photographs of musicians. These pictures of seminal and obscure musical souls are compiled in the book Somewhere There's Music (2006). Fink's deep connection with these players and their sound is roundly on display page after page. You can almost hear the phrase being rendered elastic in the shot of Thelonious Monk and Charlie Rouse at the Jazz Gallery (1961). Monk sways away from the ivories (his expression joining his nimble fingers in the articulation of a revelatory moment), while Rouse transcendentally contemplates when to reengage the master with his sax. More abstract, a rare picture of John Coltrane (1961-1962) brilliantly expresses the febrile heights of his free jazz energies as heard on recordings such as John Coltrane Live in Seattle and John Coltrane Live in Japan. Pages later, another picture of the sax pioneer appears. This time he is wearing a long coat and his body is strangely folded into the far end of a coach—his face hidden. I imagine this un-relaxed collapse happened after one of his marathon blowing sessions. While none of these photographs draws attention to the photographer, I can't help wondering: how did Fink get these extraordinary shots?

While this exciting book is a visual dunk in the deep end for jazz fans, there is a dose of hip-hop and rock on board too. Unexpected images of Jay-Z in Vegas, Lil' Kim, Bruce Springsteen and a super-clever nod to Notorious B.I.G., take the collection in interesting directions.

Remarkably, most of these pictures were done for his personal edification, without the slightest anticipation of publication. He was simply hanging out with his musical buddies, documenting the sound revolution as it sparked an unquenchable fire. Fink states, “Music runs fleshy through my veins. Music is indeed the preamble to the photographic methodology that I am known to use, which is one of great calculated speed and improvisational verve/salvo.”

Fink is insatiably curious and naturally adept at receding deep into an environment to search for and wait on poignant moments and shapes to emerge. He hunts among the shifting light, landscape and terrestrial beings for underpinnings and intentionality to subtly or abruptly surface. Another photographer's eyes may be inextricably veiled to the vitality of a quickly passing event, but he captures that nearly imperceptible private association and transfers its essence into the observable world with his camera. What he saw in open solitude becomes a shared treasure. Fink claims, “The only way to be invisible is to be absolutely visible. Secret-ism (sic) emanates its own foul smell. People often comment that you never know that Larry is there.” He insists, however, he is very present.

While Fink is first and foremost an artist's artist, he has done a lot of great commercial work, as well. Over the years, he has undertaken major photography campaigns for Smirnoff, Bacardi, Chivas Regal, Winston cigarettes and others. While highly profitable, he found this type of work extremely time-consuming and restrictive. To keep himself and his staff amused, he made as much of a party out of these stilted shoots as possible. “Advertising,” he states, “while it burnishes your soul, certainly does line the perimeters of your coffin.”

When asked which subjects he prefers to photograph or which of his achievements is his favorite, he replies, “I prefer what I am doing right now.” Fink is a creature of the moment and at 71 years old he is as busy as he chooses to be. He remains a beloved teacher at Bard College and is still globetrotting with his camera (and his third wife, artist Martha Posner). Presently he is finishing two books. One is a collaboration with Luke Sante, which brings together his political photography, tentatively titled The Political Eye, 50 Years: Photographs 1962-2012. The other is a collaboration with the poet Gerald Stern tentatively titled The Marriage between Flesh and Stone. Fink, with predictable generosity, let me have a close look at photographs from both projects. While each contains fantastic art, I was floored by the latter project. The images are unique and captivating. This is stunning, deeply engaging work.