Superheroes come in all different shapes, sizes—and costumes. Some may wear masks to disguise their identity and brightly colored suits made of Lycra. Others, according to myth, are just big and strong. Then there are the caped crusaders whom we have grown to love from the pages of comic books and Saturday afternoon matinees.

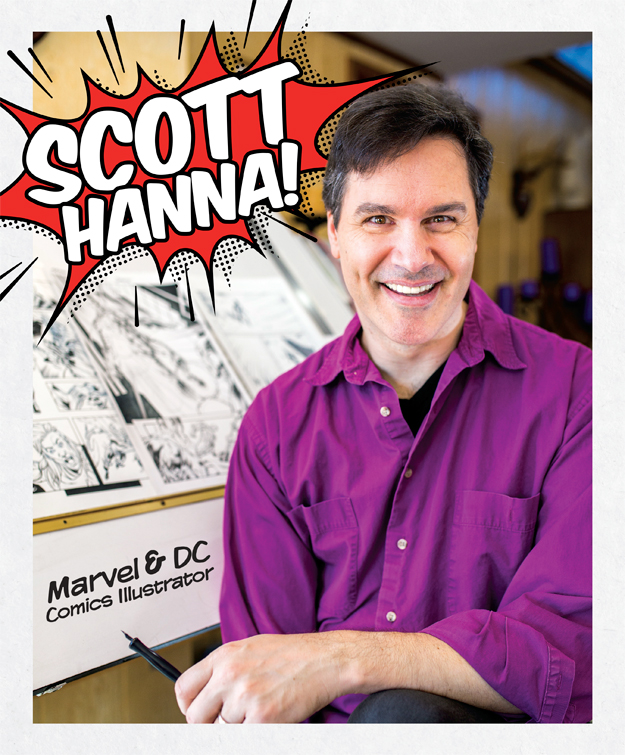

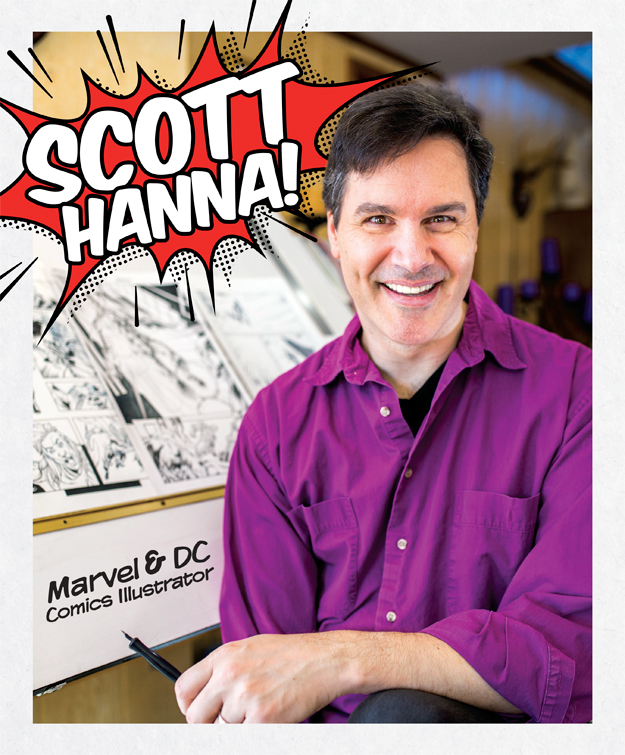

For Scott Hanna of Riegelsville, comic books have been more than a childhood passion. The fine and sequential artist has been illustrating comic book characters for the better part of 30 years, bringing DC and Marvel Comics' most popular heroes and villains to life by adding depth on the pages through the process of inking over original illustration.

The Bucks County resident's resume includes such titles as Detective Comics, Amazing Spider-Man, Spider-Man, Batman and Avengers vs. X-Men, among a slew of others. Hanna has been into art since childhood, first learning from his mother, a fine artist, who encouraged him to explore his talents. Hanna was about 10 when he discovered the comic book with its colorful characters.

Young & Restless

As he grew older, Hanna gravitated toward illustration, realizing he had a love for pen and ink drawing. Following his graduation from high school, Hanna honed his skills at the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. His initial goal was to receive a broader art education.

“I didn't think of comics as a real, adult thing to do,” Hanna says.

However, Hanna says he felt Pratt did not seem to value sequential art, as they did not offer classes in the medium at the time. But, as it turned out, his college friends were also into comics and happened to be some of the school's best artists at the time—the same group of friends who, Hanna recalls, eventually convinced some of the instructors at Pratt to rethink and reevaluate their positions on sequential art.

After his tenure at Pratt, Hanna steered away from comics and started his career in book publishing as a cover illustrator—a career path he did not particularly enjoy.

“Finally, my school buddies got me back into comics…and they knew an inker who needed an assistant,” Hanna explains.

As he learned under the inker as an apprentice, finessing his skills, he came to realize this was the type of work that he could see himself liking the most and, through it, he relived a part of his childhood.

Chance Encounter

A few months later at a small comic book convention, Hanna was making some sketches of Batman and Superman for fans when a small publisher at the adjacent booth took notice and asked Hanna if he wanted to come work for him.

Hanna accepted. It was a black and white world at the California-based Eternity Comics at first, with Hanna working primarily in pencil and ink comics, Hanna says. He gave the task of inking in those outlines to someone else initially, but quickly took back the responsibility when he didn't care for the way they turned out.

“I wanted to have the last word and for my work to [be printed],” he explains.

A marvel-ous future

Around the same time, Hanna began working for DC Comics and, eventually, the publisher's rival, Marvel. Twenty-eight years later, Hanna continues to ink for the two comic book industry leaders. He also works for a few smaller publishers as time allows. “I'll do this as long as I have fun with it,” Hanna says.

The self-described “workaholic” jokes that all he does is goof off and draw all day, but when he has a deadline, Hanna is all business—spending up to 12 (or even 16) hours working from his home studio. When he isn't drawing comic book heroes and traveling to conventions, Hanna and his wife, fashion designer Pamela Ptak, teach what they know best. The couple opened The Arts and Fashion Institute in 2011. Both have prior teaching experience: Hanna at Bucks County Community College and Ptak, a former contestant on the reality television series, Project Runway, at Drexel University.

The Arts and Fashion Institute is set up in their home studios so the students can get a sense of how the professions work in “the real world.” Working from home also allows Hanna easy access to his reference library of books and movies.

Class size is limited to six to eight students and Hanna says that their highly specialized courses are not available elsewhere in the region. Their hands-on, apprentice-focused curriculum isn't about grading for the sake of grading, either. Hanna says he will spend extra time with any student who requires it.

Hanna says he and Ptak are just natural born teachers. Not having children of their own, they especially wished to pass on their experience and knowledge to others. Practices, such as inking, will become lost art forms if they are not shared, Hanna says. The comic strip is one key place where that specialized skill is still utilized.

“I tell my students that I want to train them to be better than I am,” Hanna says. “That's what you wish for your kids. We treat our students like our kids, we want them to be the best they can be.”

There are some synergies between the worlds of sewing and comics, especially if people want to learn to make their own costumes for events such as comic book and pop culture conventions. Being married to someone in the fashion industry has allowed Hanna to learn the difference between men's and women's attire. For example, men's shirts position buttons to the left. Women's shirts place buttons to the right.

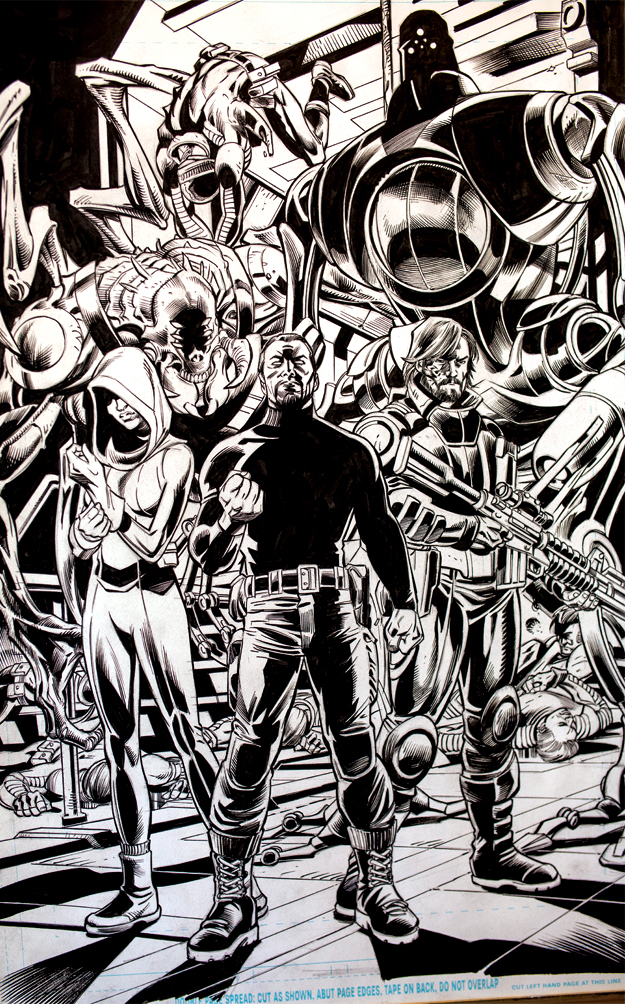

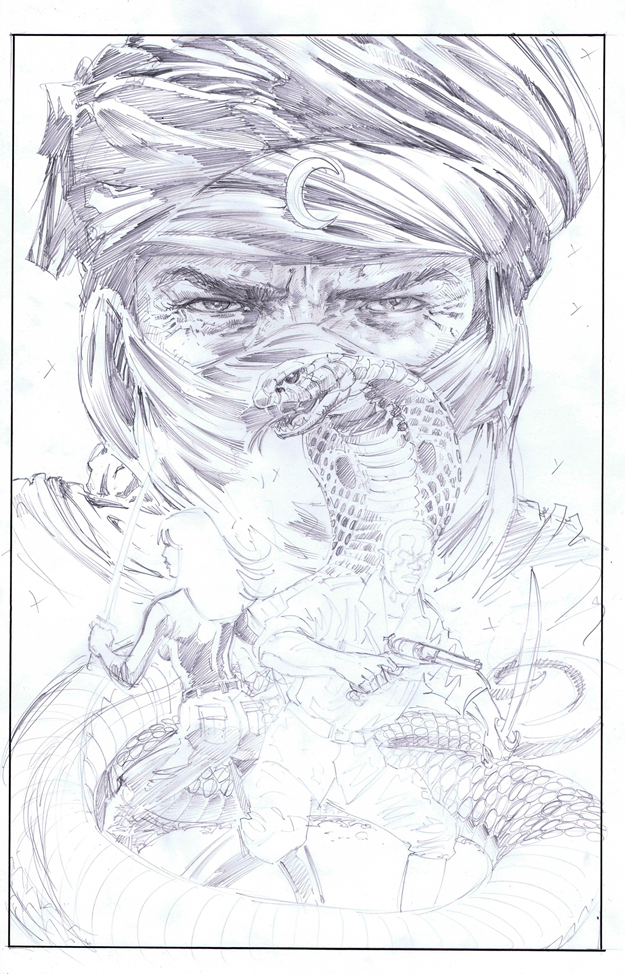

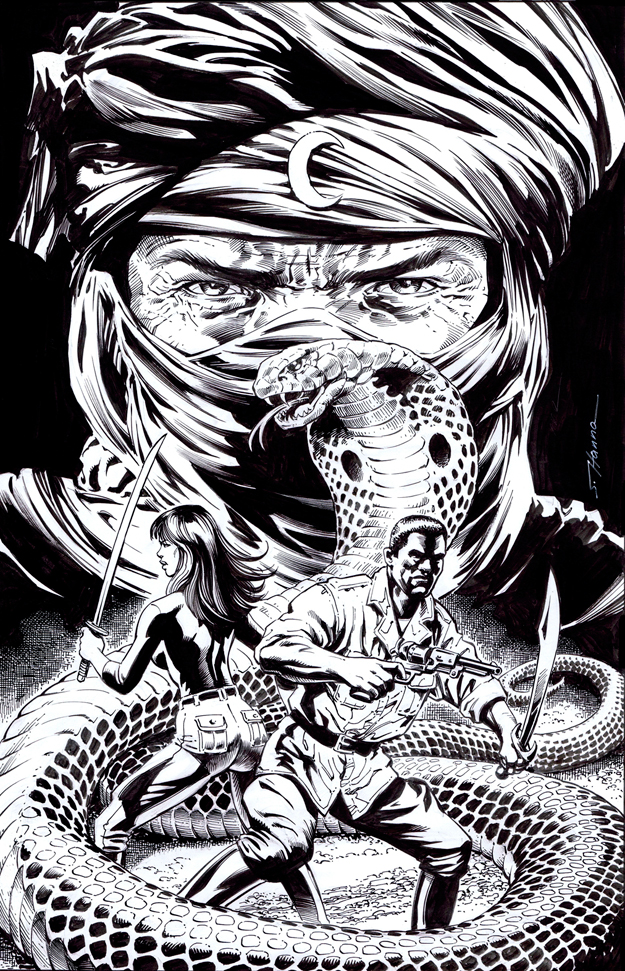

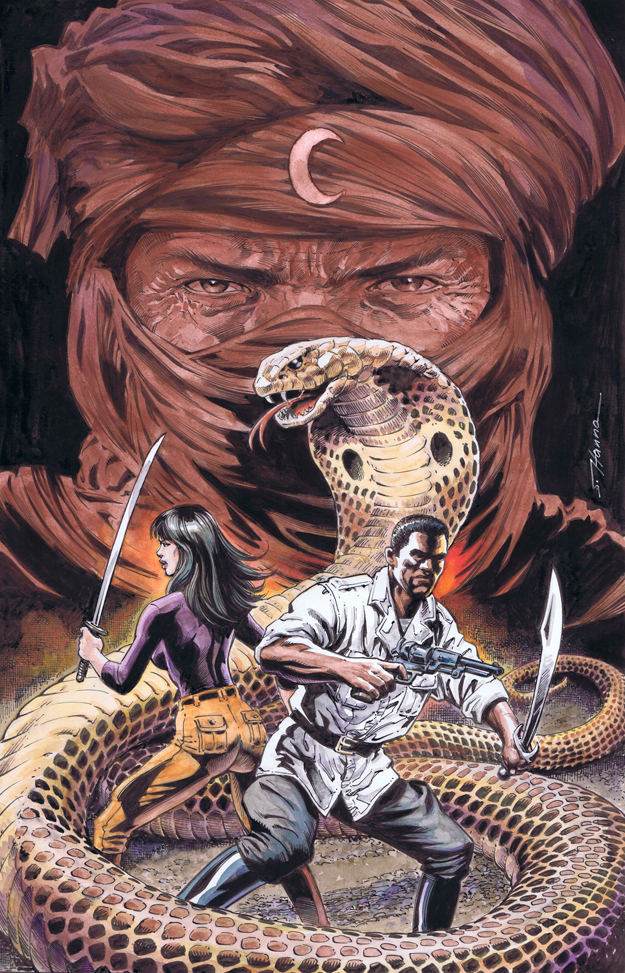

Hanna is in his element when he is at his drawing table, using his ink pens and paintbrushes to breathe life into the comic book pages. Starting from the illustrator's drawings, Hanna fills in the shading and makes the different strokes that lend texture to a piece of clothing. Occasionally he fixes a body part, like an ear, that was not big enough. He works around the page swiftly, but carefully. This is something, that for all its technology, a computer just can't do.

With digital comics becoming increasingly popular, Hanna knows there will be a point when digital sales match print sales. But collectors, he says, will always want a hard copy. Hanna says that you can't sign a digital copy and there will always be some need for the real comic book.

“I hate to say it, because I love paper,” he says. “We live in the modern world, and the modern world is digital.”

Comic books continue to endure, Hanna says, because of the morality code shared by the characters and readers. “Most people you meet, they have the same code,” Hanna says. “And most comic books have that connecting force. And that's why they still work.”

Quite the character

In his studio, there's an illustration of Batman perched on a rooftop—his favorite character.

“He is the perfect human,” Hanna says, describing Batman's alter ego, Bruce Wayne, as an Olympic-level athlete with an interest in science and plenty of money. “He's like Bill Gates fighting crime.”

Hanna says he takes inspiration from the Caped Crusader by trying to do the same with his art in being the best that he can be.

Hanna has worked on almost every character from the DC and Marvel comic book worlds. In the real world, our mighty heroes have been saving the planet for some 70 years now and would be ready for retirement, but with regular revisions of characters every 10 years or so, they have stood the test of time—spanning generations of readers. This has, in turn, helped grow the fan base over the years, and Hanna has nothing but wonderful things to say about the fans.

“They are so polite,” he says. “These are some of the best people in the world.”

Smaller comic book conventions, such as the Heroes Con in North Carolina, excite him more than the larger comic cons held in San Diego and New York City because they focus more on the artists and creators. Hanna says the larger conventions tend to also attract curiosity seekers who may have never even read a comic book.

Over the years our superheroes have tackled themes from World War II and up to more current events such as September 11, 2001. In particular an issue of The Amazing Spider-Man featured an all-black cover with just the title in white letters serving as the only piece of art on the page. Everyone involved with that issue, had, at one point or another, worked in New York City, Hanna says.

The issue, along with Heroes and Moment of Silence, both published by Marvel, helped raise money for related charities and served as a cathartic outlet for many at the Ground Zero recovery site.

“It went way beyond just drawing comic books,” Hanna says.

Silver screen superheroes

Over time, pop culture has defined how comic books are perceived. Once seen as a medium coveted primarily by the quirky reader, they are now considered a cool part of mainstream entertainment media.

The success of Marvel Studios and the expanding Marvel Cinematic Universe—including such films as Iron Man, Captain America, Guardians of the Galaxy and The Avengers—and two DC Comics-inspired television series, Arrow and The Flash, attest to that.

Hanna says he laughs sometimes when a less-versed audience member does not know what is going to happen next, admitting that sometimes, he doesn't either. Hanna says those same movie and TV audiences are changing the audience of comic books. He adds that comic book authors are typically more connected to the shows than the illustrators are, but that he can see how the shows are linked to the books.

“I think they all bring something to the table,” he says. “The TV shows bring you the love of action and special effects. The comic books give you the detailed plots and [an] ultimate budget.”

While TV shows don't have the multi-million dollar budgets that “tentpole” film franchises do, they still have to compete (the term “tentpole” typically describes the most promising industry film projects). Adapting the characters for the screen, be it silver or not, always surprises Hanna. For example, the Guardians of the Galaxy character, Rocket, is a talking, gun-toting raccoon—something easy to draw, but not as easy to adapt to a live-action film.

“It's neat to see how they achieve that,” he says.

Hanna also feels that directors and screenwriters are more interested in producing projects utilizing existing or source material, than they had in the past. “They have to make certain adaptations,” Hanna says. “How do you make them modern and relevant to an audience? How do you push the boundary?”

Comics can also be teaching tools for younger kids, Hanna says. He points out, comic books have been embraced by schools because they combine visual elements and the written word. They also use sophisticated vocabulary and concepts that can span from political stories to racism and war.

Because comic books were initially designed as a throwaway item, the older books became scarce so they are worth money today, Hanna explains, saying his own father traded them with his pals in the neighborhood when he was just a boy.

Hanna is even excited when he receives the print version of a book that first published digitally.

Hanna says he will never retire from art. He says artists never really retire from their craft—even if it means spending his last day on Earth at the drawing table.

“You do it until you die,” Hanna says.

Cowabunga, Batman! We hope that won't be for a long time!

The Process of Making a Comic Strip or Book

1. A writer develops a script with story and dialogue.

2. A penciller does the initial layout and rough or detailed drawing in pencil.

3. An inker finishes the drawing with ink to make it print-ready, adding detail, texture and line weights.

4. A colorist then adds all the color and effects to the line art.

Note: Hanna's specialty is inker, though he sometimes does pencilling or color.

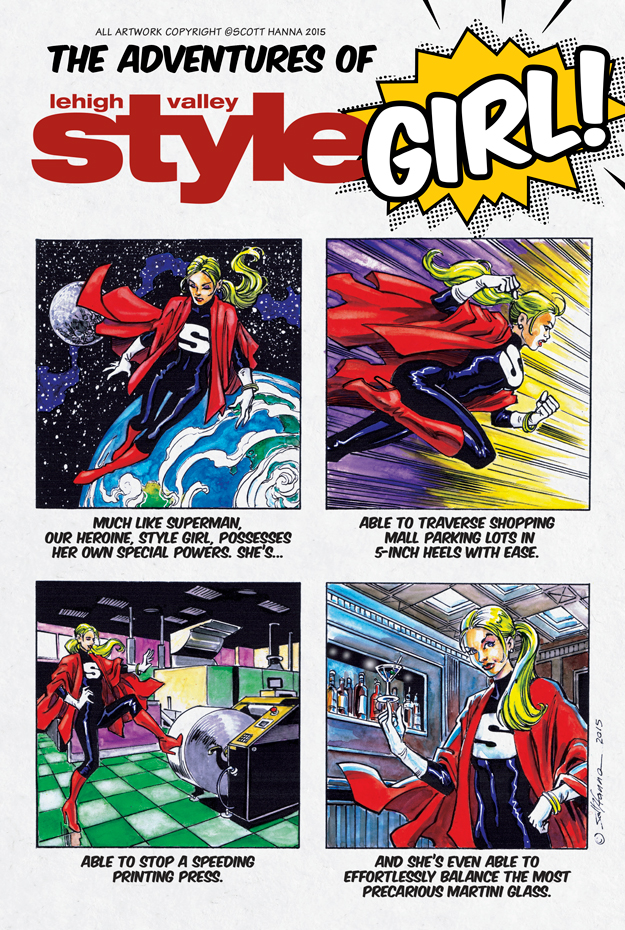

All artwork copyright ©Scott Hanna 2015